How to improve building energy performance without up-front capital

Air-conditioning equipment, office furniture, lighting systems and even floor coverings are being leased, so why can’t a building façade upgrade follow a similar business model?

Most post-war construction in Europe occurred quickly and cheaply, providing building stock only fit for a few decades of service. Energy conservation and energy efficiency were hardly ever considered. As a result, many buildings are now at the end of their useful life, consuming huge amounts of energy while being expensive to maintain. A third of Europe’s CO2 emissions now come from the built environment and these urgently need reducing, along with the construction sector’s overall environmental footprint.

Vast numbers of buildings across Europe need renovating. However, retrofitting existing buildings is a difficult and costly process, and the potential benefits are hard to quantify. As a result, many owners and managers are reluctant to make upgrades and the integration rate of technologies that enable energy-neutral or low carbon buildings is painstakingly slow. This is frustrating, especially given that renovating building façades, otherwise known as building exteriors, or ‘envelopes’, offers a lot of potential for improving efficiency and reducing emissions.

Is there a way to incentivise building owners and managers to upgrade and improve their building’s energy performance without having the up-front capital to do it? After all, air-conditioning equipment, office furniture, lighting systems, and even floor coverings are being leased, so why can’t we get the upgrade of a building’s façade to follow a similar business model? This is the central question of the Façade Leasing project, which brings together academics at the Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment at TU Delft (‘Delft’), the bank ABN AMRO and key façade manufacturers in The Netherlands.

A circular economy approach, where building components are constantly replaced with newer, more efficient ones and older ones are re-used, can both reduce emissions and cut costs. Implementing this kind of approach is best achieved by focusing on building façades, which not only separate interiors from the outside world, but play a vital role in the energy performance of building services, such as heating and lighting, and can account for up to 95 per cent of renovation costs.

Façade leasing

The Façade Leasing project road-tests integrated facade technologies that improve building energy performance and looks at how to change established economic, legal and managerial practices to incentivise the construction industry to function as a circular economy.

It proposes using a ‘services and systems’, or a leasing approach, in which building façades are leased to property owners. This means that the façade supplier is responsible for maintenance and upgrades and incentivised to keep them as up to date and energy efficient as possible, thus preventing depreciation and encouraging re-use and materials recycling.

Pilot project

Those of you who have worked in innovation will know the graveyard is full of pilots that have gone nowhere, and this project is at that stage: ‘We have done it, we have built the pilot, now—how do we scale this idea?’ In 2016, the team showcased a wide range of façade-integrated services and tested their capacity to deliver indoor comfort regulation on four unitary curtain wall panels on the building of the Electrical Engineering, Mathematics and Computer Sciences faculty at Delft (see image below). This enabled them to test technologies such as exterior sun-shading systems, ventilation and air-handling devices, LED media elements and automated operable windows.

This pilot also acted as a case-study to discuss the implications of the proposed leasing model, especially its financing, legal, managerial and supply chain implications with key actors, such as real estate investors, façade fabricators and system suppliers.

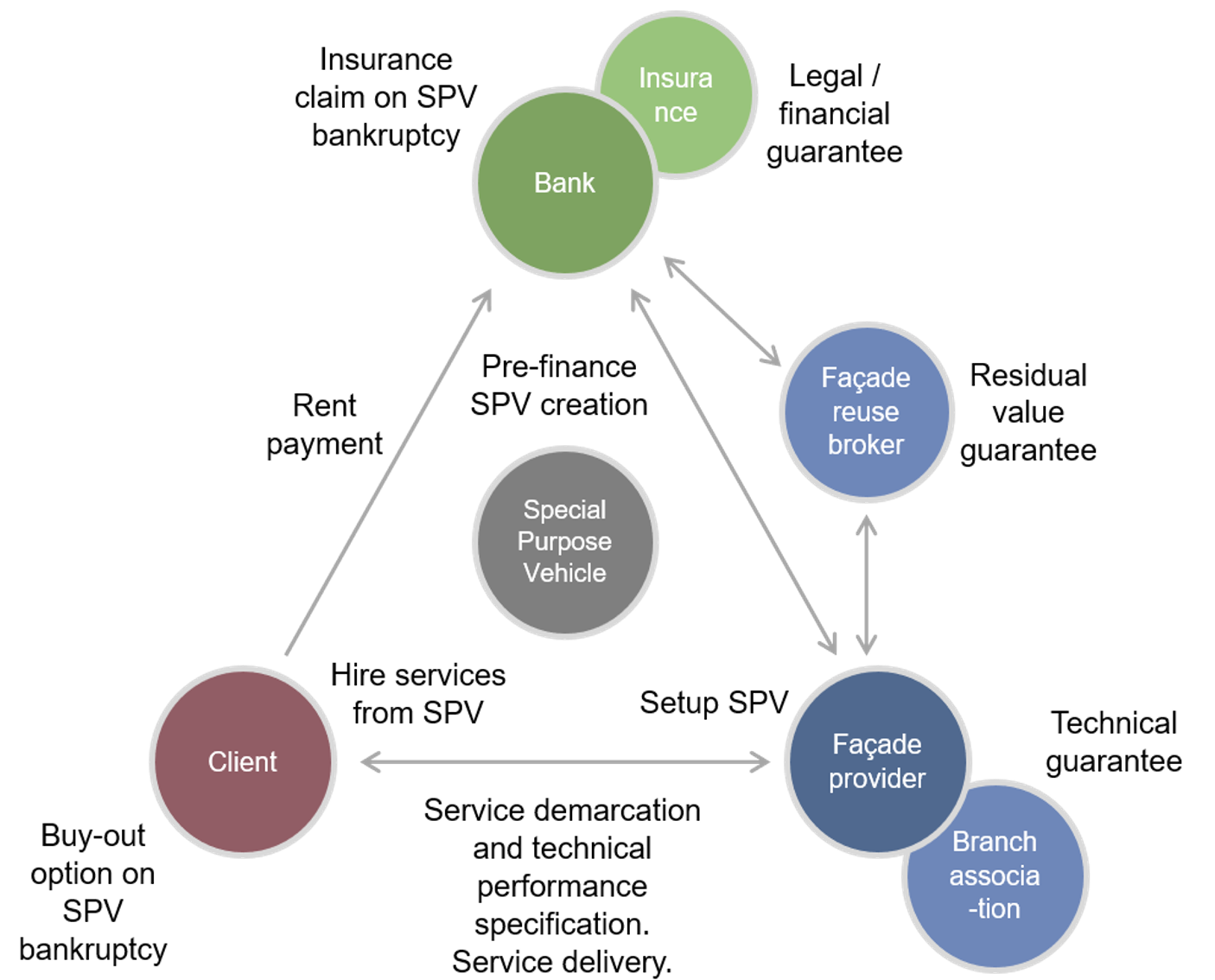

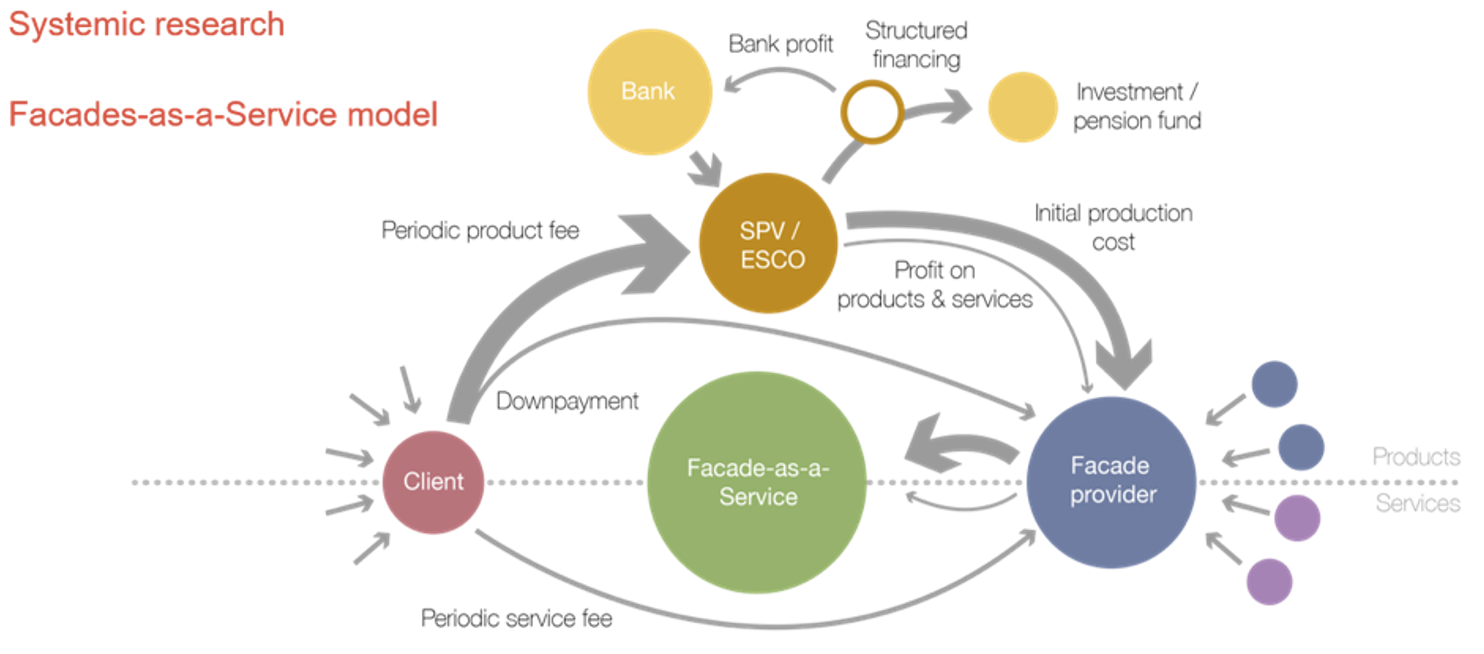

For example, project financing for construction is typically secured by the market value of the property being financed, not by the provision of ongoing services. To tackle this, the team worked with Dutch bank ABN AMRO to produce an innovative financing mechanism where cash flows from façades work as bank guarantees. Similar new solutions were found to counter legal and managerial challenges, for example to allow the façade provider to retain legal ownership of the façades once they are integrated into the building. A business model was developed, and it looks like this:

While performance contracts and product-service systems have been implemented in the consumer product, automotive and construction sectors, the idea of applying such a model to the contracting of energy-efficient building envelopes is original to the project. The uniqueness of the proposed contracting model lies in the level of practical implementability. Legal and financial hurdles—such as the division of legal and economic ownership, and a working financial and contractual structure tying all project partners together throughout the project’s long-term service-life—which, so far, hadn’t been addressed by similar initiatives, have been solved during the project, thanks to Climate KIC’s support.

Demonstrating the solution

Having identified the most appropriate technologies, and workable managerial, economic, legal and financial mechanisms, the team worked to create a large-scale façade on the side of the Department of Civil Engineering at Delft. This is a huge building housing 300 employees, with 3,000 square meters of façade that is reaching the end of its service life. It provided an ideal case study for a ‘real-life’ test of the proposed technologies and leasing model. Construction was carried out on-site between July and December 2019.

Every new high-performance façade panel for this building is made of high-insulation aluminium framing and HR++ double-glazing and was delivered in a pre-assembled format, making it easy to install. Panels include automated sensors that drop-down solar screens during intense sunlight and high temperatures and pull the same screens up in wet and windy weather. Upper-level windows are automated to enable passive ventilation and night-cooling and a QR code on each panel keeps a history of maintenance schedules. These codes also collect data to allow the team to study the new façade’s impacts in terms of, for example, energy expenditure and indoor comfort.

A manual was also created to help building users get involved with the project and understand the new façade functionality. This provides clear illustrations of how, for example, the wind and rain sensors and temperature controls work, and how to manually operate the solar screens.

Early results indicate that the Department of Civil Engineering at TU Delft façade renovation has been a great success. Primary energy use has fallen by around 75 per cent, from 189 kWh/m2 to 48 kWh/m2, saving between €35,000 and €40,000 a year. Users are also reporting improved air quality and a more pleasant work environment, thanks to the solar shading. These is the potential for massive savings should this solution scale across Europe.

The team also made solid progress using this case study for testing the leasing model. While further research and validation work is needed, it’s now very clear that a circular economy approach is achievable within conventional legal and economic frameworks.

Legislation supporting the Façade Leasing approach remains vague, due to the complexity of designing policy that will keep construction costs low, but still deliver sustainability benefits. However, limiting virgin materials use and promoting the high-value reprocessing of components is continually emphasised in academic and professional circles.

With the technology tested and many other initial headwinds solved, the challenge now is how to bring the Façade Leasing solution to market. It has already been presented at building industry conferences and several potential customers, including a housing association and a corporate entity, have already expressed interest.

So far, Façade Leasing has proven to be an excellent potential solution for upgrading buildings, reducing emissions, cutting costs and implementing a circular economy.

For Façade Leasing to scale, a few things are required.

- A business model that is willing to take a long-term view ‘patient capital’, that is willing to look at not only the energy costs, but the improvements in occupant performance from being in better performing buildings. The pilot building was boiling in summer and freezing in winter. This new façade has had a positive effect on occupant performance.

- A new breed of investors and ESCO type contractors, that are willing to take on the building envelope’s performance. The monitored pilot has shown the reductions are huge.

- Policy makers that are willing to go bold with build performance and legislate if necessary, to get communities of buildings significantly reducing their carbon burden.

- Property owners (and this includes universities that tend to own their own buildings and have a typology very similar to the one shown in TU Delft) willing to scale this solution. With economies of scale and systemisation the costs of undertaking this work will reduce. Look at what happened to the cost of PV cells for example where the costs are half what they were five years ago because the global demand.

- The façade industry, willing to enter this market.

If you’re reading this and it sounds interesting, please get in touch by emailing facadeleasing@tudelft.nl and we would be more than happy to share the findings and the business model. Help us share this idea around the world, so it doesn’t end up another pilot that had potential, but the scaling couldn’t be unlocked.

[bctt tweet=”Air-conditioning equipment, office furniture, lighting systems, and even floor coverings are being leased so why can’t we get the upgrade of a façade of a building to follow a similar business model? #energyefficiency ” username=”ClimateKIC”]