Innovating in complexity: Systemic investing

It is a document of only 56 pages—but its brevity is no indication of its aspiration. What the “Roadmap Towards the Circular Economy” articulates is one of the most ambitious visions for a nation-state to meet the objectives of the Paris Agreement: Make Slovenia, a small nation located in southern Central Europe, the first country in the world with a fully circular economy.

The Roadmap answers the call from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) for the “rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented” transformation of the socio-technical systems that form modern human civilisation: National economies, regional transportation systems, infrastructure clusters, industry supply chains, and cities. It paints a future in which Slovenia is energy self-sufficient and manages natural resources efficiently, thrives on green jobs and international competitiveness, and offers high quality of life to its citizens. If accomplished, these goals would change the face of the country and offer a blueprint for others to follow suit.

As remarkable as the Roadmap’s vision is, even more astounding is how the document sets out to accomplish that vision. Instead of presenting a linear and deterministic plan, the Roadmap acknowledges that the transition to a circular economy is a “complex, comprehensive, and long-term process” that calls for a “new way of collaboration, involvement, exploration, learning, and innovation.”

It tells the story of a brighter future for all. It kindles a sense of adventure, gives hope, and inspires action, which is exactly what roadmaps are good for.

But how exactly should Slovenia go about pursuing its vision?

National economies are complex adaptive systems that require a radically new model of innovation—a collaborative and exploratory approach that intervenes in multiple domains of a system through a portfolio of deliberately chosen innovation experiments.

At Climate KIC, where I work, we define such systems innovation as integrated and coordinated interventions in economic, political, technological and social systems, and along whole value chains. Central to this innovation model is the engagement of multiple levers of change within a system. By that we mean technology, policy and regulatory frameworks, business models, social norms and behaviors, skills and capabilities, individual and collective narratives, and production and consumption paradigms.

Yet there is one particularly powerful lever spanning all of these domains: Money.

The way in which capital accumulates and flows through a system has a tremendous impact on how the people within that system behave. This creates an opportunity for change agents in Slovenia and elsewhere to harness the power of capital in service of a transformative vision.

But what happens when we marry the discipline of systems thinking with the practice of capital deployment? How do we have to rethink the central concepts of investing? And what knowledge and capabilities do we need to operationalise such an investment logic?

The building blocks of systemic investing

I define systemic investing as the practice of deploying capital to catalyse directional transformative change of socio-technical systems.

There is a lot of jargon in this definition, so let me unpack it.

The importance of intent

The heart of systemic investing—and also the defining difference to traditional investment—is intent.

Today’s financial industry is driven by a singular objective: Multiplying financial capital. In other words: Using money to make money. In contrast, systemic investors intend to use capital primarily to create change dynamics that propel a system in a specific direction.

This directionality is set by the transformation agenda of a challenge owner such as a government, a multilateral organisation, a foundation, or a corporation. Economist Mariana Mazzucato of University College London calls such transformation agendas missions.

Prioritising mission-oriented impact doesn’t mean that systemic capital must forgo any financial rewards. In fact, it is possible to both create systemic impact and generate an acceptable risk-adjusted return.

Yet intent is essential because what investors set as their priorities determines what they care about. Systemic investors will interrogate the universe of investable assets with different frameworks, using different metrics to evaluate potential, success, and failure. They will also bring a different spirit to their investment practice, embracing collaboration over competition. In short, systemic investors will engage with a different mindset.

Are these just philosophical musings? Not at all.

Mindsets matter because complex challenges are shared challenges. The culture of today’s financial industry is dominated by notions of competition, tribalism, exclusion, and ego. These values fundamentally sit at odds with the notion of a sustainable and equitable world.

To have the opportunity to generate truly transformative impact, investors must value and promote collaboration, community, inclusion, and humility. They must accept responsibility for their action, recognising the power of individual agency to solve—or perpetuate—the problem.

Understanding evolutionary possibility

Intent and mindset clarify the “why” of systemic investing. The quest for understanding how starts with mapping the system we want to change. This means identifying and characterising the nodes and relationships within a system as well as its behaviors and dynamics. It also means getting to grips with the material and financial stocks and flows, and with the actors that control these.

Creating a map of the system, even if only as a fleeting hypothesis, provides a useful starting point for identifying the investable universe. This universe can be clustered in real-economy categories such as infrastructure, businesses (start-ups, SMEs, and large corporates), and risk transfer mechanisms (e.g. insurance) along with associated asset classes such as equity, fixed income, real estate, commodities, derivatives, and cryptocurrencies.

So how does change within complex adaptive systems happen?

Systems move from one state to a future state through an evolutionary process. One of the marvels of evolution is that it produces a great variety of designs that are fit for a specific purpose. Just consider the myriad of ocean creatures fit for the purpose of swimming. For the same reason, there is a multitude of different “system designs” that could accomplish a specific mission. What counts is not to perform a precision landing on any individual design—but instead to arrive somewhere within a general landing zone.

In the context of climate change, for example, that landing zone is typically described as “low-carbon and climate-resilient”. What this means exactly varies by context. It is neither useful nor practical to articulate a highly specific end state. Instead, systems should be given the freedom to express themselves in whichever way is fit for their specific context, provided that they land within the zone.

There is, however, one thing that is important to keep in mind when defining the landing zone—systems are path-dependent. Where they have been in the past matters for where they can go in the future.

As economist Eric Beinhocker explains in his book The Origin of Wealth, a system can only evolve toward a new design if there are intermediate niches that act as developmental bridges between the old design and the new design. If the two designs are too far apart, the system cannot just “jump.”

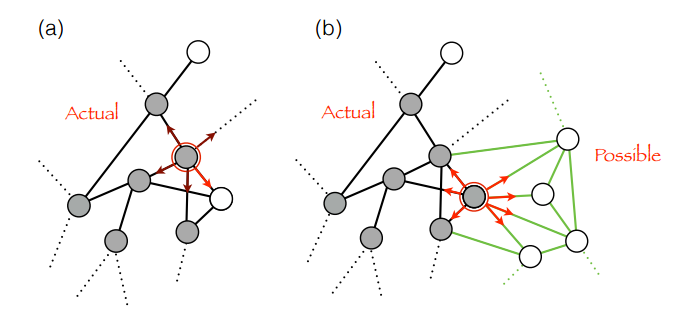

In other words, transformations don’t occur as discrete phenomena that happen in an instant, like flipping a light switch. Instead, they progress along a gradient, evolving forward through a series of what complex system scientist Stuart A. Kauffman calls adjacent possibles. These are spaces of possible future states that originate in the system’s past and represent a (concealed) menu of all the ways in which a system can reinvent itself.

So systemic investors must understand the transition pathways a socio-technical system could reasonably take, given its current resources and configurations. We find this thinking expressed in Slovenia’s Roadmap when it speaks of the need to “know Slovenia intimately and understand what [the country’s] competitive advantages are.”

To travel along that dimension and move from one adjacent possible to another requires a transformation strategy—a plan for intervening in the system in a way that compels actors to behave in the right kind of way.

Leveraging system dynamics

This still leaves the question of what to invest in. We know, from both theory and practice, that certain interventions in a system have greater potential than others to cause the system to change. Donella Meadows, a pioneer in systems thinking, calls such high-potency interventions “leverage points.”

Applying the concept of leverage points to investments is still in its infancy. Yet there are some well-understood effects that provide useful starting points. For example, the neighborhood effect describes the phenomenon that people become more likely to adopt a new technology if their neighbors already have it. Similarly, the halo effect occurs if newly built public goods increase the value of nearby properties, which happens routinely with the arrival of supermarkets and parks.

Perhaps the best-understood concept is tipping points—defined as thresholds after which runaway change propels a system to a new state.

In the context of mitigating climate change, tipping points can be observed in the adoption of renewable energy technologies. As a technology slides down its cost curve—typically propelled by economies of scale and experience effects—it eventually reaches cost parity with incumbent technologies. After that point, its uptake accelerates significantly.

The key question for systemic investors is: Where could a relatively small investment trigger a larger change that becomes irreversible, and where non-linear feedback effects act as amplifiers?

A group of researchers at the Oxford Martin School calls these places Sensitive Intervention Points (SIPs). They differentiate between two kinds. The first involves a kick to the current state of the system, moving it onto a new trajectory without any change in the underlying system dynamics. For example, governments could subsidise renewable energy technologies that are close to tipping points. The second involves a shift in the underlying system dynamics, where the rules of the system itself change. This may include a change in key concepts or institutions such as the move from the rigid Kyoto Protocol to the more flexible Paris Agreement.

In either case, the goal is to design purposeful interventions that drive nonlinear amplification in complex systems, including through investments in infrastructure, technology start-ups, insurance products, public subsidy schemes, or other capital deployment mechanisms.

Strategic portfolios: Blending for synergistic effects

Yet in complex adaptive systems, it is rarely a single intervention that pushes the system past a tipping point. Instead, fundamental change is often the result of multiple forces acting together. This creates an opportunity for systemic investors to compose portfolios of assets that can mutually reinforce each other’s impact potential.

What matters in constructing such strategic portfolios is not so much an individual asset’s merits but its potential to unlock or accelerate transformational effects in combination with other assets in the portfolio. In other words, the key is to create strategic synergies for producing the right type of change dynamics with respect to the transformation agenda. This implies a move away from the single asset paradigm—one stock, one bond, one project—that dominates today’s investment practice toward a strategic blending paradigm.

Where capital alone is not enough to unleash transformative dynamics, systemic investors should align themselves with actors engaging other, non-investable levers of change in the system, such as policy and education. Oftentimes, these are public sector actors or philanthropic organisations. The purpose of such nesting is to ensure that the portfolio of real economy assets is well aligned with a broader set of systems interventions, all designed for their collective, synergistic ability to generate transformative dynamics.

Consider a city intending to electrify its transportation sector. Policy aimed at shifting the relative economics between EVs and fossil fuel-powered cars and creating consumer awareness will likely be more effective if the private market concurrently invests in charging infrastructure and roof-mounted photovoltaic systems.

Likewise, those investments will have more compelling risk/return characteristics if they are made in the context of a government-led “market shaping” effort. In other words, such public-private investment partnerships have the potential to fundamentally de-risk the private sector’s investment activity—creating a compelling argument for rethinking the way value is generated and shared, particularly between public and private actors.

Evaluating performance

In any uncertain endeavor, what constitutes risk and reward depends on what one wants to accomplish. In traditional investing, where the primary intent is the multiplication of capital, success is typically measured as the extent to which that multiplication happens. The key metric is financial return on investment (fROI). Risk, then, is defined as the quantifiable uncertainty that such a return actually materialises.

Systemic investors, who are primarily interested in transformative change, will require a new conception of risk and return; one defined in relation to their transformation agenda. The key metric is transformational return on investment (tROI).

In some cases, it will be possible to measure success using well-known indicators. For instance, in its 2017 annual report, the UK Green Investment Bank states that its renewable energy investments will generate an estimated lifetime reduction in CO2-equivalent emissions of 154 million tons. Yet the energy system is a relatively neat system, with rationale investors, predictable technological performance, mature supply chains, and well-functioning markets.

Other domains of human civilisation—such as transportation, industry, and cities—are messier because of the human agency that sits at their core. When intervening in these systems, outcomes can often not be attributed directly to any specific intervention, let alone be expressed in a quantitative metric. The cause-and-effect relationships in these systems are simply too opaque, and the latency between action and impact is too long.

Moreover, systemic investors don’t need to provide all the capital required for a system’s transformation. They only have to lead it to its tipping points, after which the system’s feedback loops will cause it to self-organise around a new orthodoxy hat economist Carlota Perez describes as a “common-sense economic logic”. In that sense, what matters is an investor’s impact on the transition dynamics unleashed in the system of interest.

So how can such transition dynamics be measured?

The beginning of an answer is offered by the Transformative Innovation Policy Consortium (TIPC), which has started to develop an evaluation framework for transformative change in the context of innovation policy. Frameworks like these can be adapted to the specific context of investment, offering a new lens through which to conceptualise investment return.

This, in turn, paves the way for developing a new definition of risk. What matters to systemic investors is the uncertainty of achieving their transformation agenda. Risk can thus be defined as the quantifiable uncertainty of unleashing no transition dynamics, or the wrong ones. A definition of this kind will naturally lead to a different approach to risk management, following the adage what gets measured gets managed.

Engaging emergence

As the interventions in the system take hold, the system will inevitably start expressing properties that the individual actors don’t embody. System scientists call this phenomenon emergence.

Systemic investors need to be proficient at observing what’s happening in the system and at making sense of its behaviors and patterns. Emergence acts like a window into the future, giving cues where the system might develop desirable trends that investors can reinforce.

Engaging with the emergence of systems implies that systemic investors need to rethink the concept of asset allocation. Today, such asset allocations are relatively static constructs, designed once and mainly as a function of an investor’s asset base and risk appetite. Systemic investing requires a more dynamic understanding of asset allocation. It requires an idea of what the strategy consultancy Axilo calls “optimal capital allocation”—right-sizing the investment portfolio for a specific mission. It also necessitates the patience required to spread investments over time as well as the ability to dynamically adapt the asset mix in response to the revelation of leverage points.

The promise of systemic investing

Article 2.1c of the Paris Agreement calls upon the world to “make financial flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development.” What that means from a practical perspective remains largely unclear.

Nor is it obvious how today’s most prominent sustainable finance initiatives—such as ESG investing, the triple-bottom-line approach, socially responsible investing, divestment, or impact investing—can build a bridge to the IPCC’s call for real-economy transformations at the scale and pace required.

The world faces a massive investment gap to achieve a transition to a more sustainable and just society. While estimates of that gap vary by source, the consensus is that it reaches into the trillions of Euros per year.

Given how little time we have to reverse our emissions trajectory, there is now an urgent need to rethink the way we will deploy capital over the next decade. For not all money must be a passive entity in society, flowing to whatever opportunities emerge in the real economy. If we want to succeed at coping with today’s gravest challenges, some of that money can—and must—become an active agent of change, carving the landscape of real economies to create more sustainable “basins of attraction” for passive, rent-seeking capital.

Transformation Capital is not a sure-fire recipe for driving this kind of change. But there are several reasons why it holds the promise of being more effective than the traditional investment orthodoxy at deploying capital for transformative effects.

By intending to transform systems for greater sustainability, equity, and justice, its goals are more consistent with the aspiration to safeguard human civilisation than the money multiplication motive of traditional capital.

By acknowledging economies as complex adaptive systems, it is more in tune with the fundamental nature of our world than the predictive mathematics and decision-making frameworks of present-day investment managers.

By assigning an active role to capital for shaping our future, empowering decision-makers in the real economy, and emphasising individual agency, it is more immediately actionable in the real-world contexts that matter than investment approaches focused on risk avoidance, secondary markets, and institutional frameworks.

By focusing on strategic portfolios and collaborative partnerships, it is more likely to unlock change of the type we need than the single asset paradigm of today’s investment professionals.

None of the above will mean anything unless its theory is put into practice. This is why Climate KIC is currently designing the Transformation Capital Initiative. Its purpose will be to develop and test the conceptual underpinnings of systemic investing. If you are keen to shape an investment logic capable of addressing the most pressing and tangible problems of our time, we want to hear from you.