This article is part of the Futures in Long-termism series. You can read all other related blogs by following the links at the bottom of the text.

Our wealth and income, as individuals, depends on the efforts and achievements of the many generations who came before us. However we tend to underestimate our relationships and lineages with past generations and future populations. This is due to our systemic and psychological inability to perceive our lasting footprints beyond our deaths. How can we establish an understanding of self-hood that persists across time periods to recognise our influence and provide and care for our future relatives? Persistent Selves attempts to investigate why we are unable to perceive the continuity of our actions well after our death and why we are not adequately concerned with the fate of multiple successive generations.

In 1978, sociologist Elise Boulding said, “Modern society is suffering from temporal exhaustion. If one is mentally out of breath all the time from dealing with the present, there’s no energy left for imagining the future.” More than 40 years later, the present commands an ever greater attention from all of us—most evidently we live in the age of the Attention Economy fueled by social media platforms that preoccupy us with the immediate past (eg. Instagram) or the immediate future (e.g. personalised ads). As Fred Polak suggested, “Our time only knows a continuous present.”

In its most violent form, temporal exhaustion affects populations during financial crises, increasing the number of suicides and deaths due to mental and behavioral disorders. Escalating economic inequalities are hindering our capacity to care for ourselves, let alone for future generations. As another study indicates, populations that live in poverty tend to make poor long-term financial decisions because their economic situation makes it difficult to focus on anything but the short-term. Under these circumstances, the lipstick effect—a term describing the behavior among people with shrinking disposable income to seek small purchases to treat themselves in the immediate present—is indeed a worrying aspect that can impede on our psychological ability to engage in acts of long-termism.

Returning to Boulding, she proposed a simple solution to temporal exhaustion: “Expand our idea of the present to two hundred years—a hundred years forward, a hundred years back. A personally experienceable, generations-based period of time, it reaches from grandparents to grandchildren—people to whom we feel responsible.” But even if we manage to experience psychological relevance before and beyond our lifetimes, our current systems are limiting us in making acts of care at such timescales.

Let’s look at our inheritance instruments, the edifice of the law of succession has tremendous social and legal importance. Succession includes the law of wills, intestacy, trusts, charitable foundations and the law concerning death taxes. Under the freedom of disposition, property owners have the nearly unrestricted right to dispose of their property as they please. There are some restrictions over transfers, like wealth-transfer taxation, but even these limits have been weakened by legislation, with instruments such as life assurance, discounted gift trusts and lifetime gifts taking advantage of loopholes. The result is the accumulation of resources in the hands of the few. Currently, there are 618,000 Millennial millionaires, with more on track to inherit from the richest generation ever, while income inequality has been rising since the 1970’s, disproportionately allocating resources. Our inheritance instruments are making large populations poorer and incapable of dealing with the future.

Most importantly, our legal rites of passage focus too much on monetary wealth, which has become the dominant way of caring and securing future populations. But some of today’s troubling issues, such as the extinction crisis, cannot be represented and addressed in monetary terms and will require different means to ensure the survival of our future generations.

What will it take to break free from our short-sighted and money-oriented inheritance behaviors and instruments? How can we be altruistic enough to care about people we might never live to see? How can we construct post-mortem interactions with our future generations?

Experimental probe: Willed futures

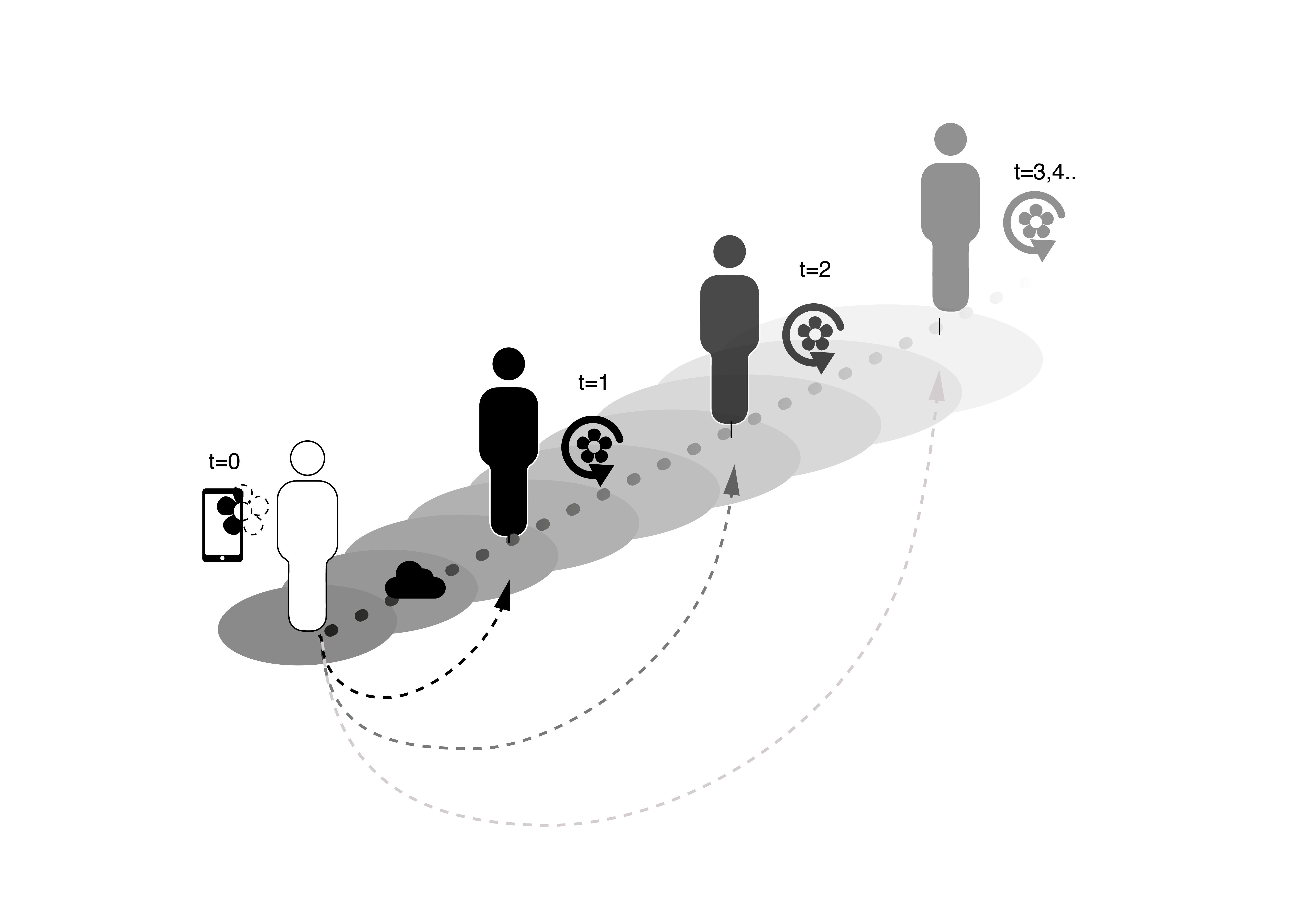

Willed Futures is a platform that automates acts of care that transcend death. Users are able to send a flower every year to a loved one after the moment of passing, extending the presence of self-hood well beyond bodily material decay, by digitally coding and planning gestures of generosity that are executed in the afterlife. By stretching the ability to plan future interactions with cherished individuals we can start to understand our capacity to affect future generations. Most importantly, Willed Futures allows self-hoods to persist in a format beyond just mere capital wealth, providing the potential to establish intergenerational inheritance systems that unleash a freedom of care and slowly direct humans from an individual concern about life to a collective view of the world.

There’s already a growing conception of inheritance beyond mainstream capital transfer instruments, that has appeared as a result of our species’ uncertain future. Countries are becoming increasingly aware of intergenerational inequalities linked to natural resources—India is the first country to acknowledge that minerals are a shared inheritance and a source of wealth that future generations should have an equal right over; and is considering adopting a 21st century mineral policy. At the international level, initiatives such as the Rights for Future Generations, have formed due to the threats of climate change and are attempting to construct conversations to advance environmental protections for future populations. Other movements, such as the Resource Generation, argue for a redistribution of wealth, land and power from classes of privilege towards the under-privileged, in order to support intergenerational social justice and solidarity.

The above efforts are a way to address future insecurities by planning for longer timescales. In this context, inheritance is framed beyond the lifetime of a human towards geological time; ecosystems, natural resources, civic capital, and community ties become important elements to be preserved and passed on. This shows, we need to expand our notion of inheritance and that it’s essential to construct acts of solidarity in different forms and formats for future generations.

But we also need to expand the capabilities of our human psychology in imagining and constructing intergenerational inheritance practices. Behavioral evidence shows that as we grow older the ability of our brain to encode ‘a wide variety of anticipated rewards, including learned rewards such as money or social rewards increases. This ability is enhanced if our neural mechanisms mediating future-oriented mental processes are engaged and if we’re presented with personally relevant information during decision-making processes. This means, we’re more likely to appreciate the value of caring for future generations, and the benefits of long-term thinking, if we can imagine a personally relevant future.

Our experimental probe, Willed Futures starts at this point, to create self-hoods that are dynamic ever after the moment of death. To do this, we’re taking advantage of the possibilities opened by digital personas that can help us to imagine our agency ever after our lifetime and as a result trigger decision-making behaviors that consider long-term effects. For example, the Digital Legacy Association has designed a platform to help deal with the afterlife of our digital footprints. Users can download a social media ‘will’ template, a witness-signed statement of preferences designed to address each online ‘terms of service.’ Tributize, on the other hand, acts as a permanent greeting card after the moment of death. Taking further the capabilities of these technologies we want to ask: Could a digital platform that reframes our understanding of inheritance nudge us towards future-oriented thinking and would it motivate us to make acts of care, reconciliation and generosity for future populations?

This is one of another six interdependent experimental zones and probes we’re investigating as part of our work on Futures in Long-termism.

You can read more here:

1. Perishable Selves to Persistent Selves

2. Obsolete Objects to Persistent Things

3. Abstracted to Entangled Organisations

4. Shrinking State Care to Long Welfare

5. Short-term Investments to Long Financing in a volatile world

6. Limited Representative Democracies to Long Democracies

These pieces have been co-authored by Chloe Treger, Indy Johar and Konstantina Koulouri. The visuals were developed by Juhee Hahm and Hyojeong Lee.

This portfolio of experimental probes is part of broader system of interventions being prototyped by the Long Term Alliance.

The Long Term Alliance is co-founded by EIT Climate KIC, Dark Matter and a cohort of partners focused on five Areas of Action, which when combined seek to leverage systemic impact—changing behaviour, mindsets and action towards a long-term oriented society.

Our five Areas of Action are: Resetting the Rules of the Game for Regulation and Governance; Rethinking Notions of Value to Reform the Financial System; Empowering Individuals through Information Transparency, Capability Building & Behaviour Change; Enabling Collective Action & Creating New Democratic Spaces to Create the Ground Swell Pressure for Change; and Shifting Culture & Narratives to Promote Long-Term Mindsets.

In parallel and in recognition of the scale of change necessary, EIT Climate KIC together with Dark Matter and our partners are also experimenting with new instruments, mechanisms and vehicles that can invest over longer time frames, invest in the institutional deep code experimentation necessary, invest vertically in portfolios spanning deep culture change to new institutional infrastructures to accelerate the transition of Europe towards a long-term society.