The tyranny of categorisation

Humans have an obsessive compulsion to categorise. While categorisation is a natural and necessary mechanism to cope with the complexity of our world, it perilously inhibits our ability to address the most pressing and tangible problems of our time.

I work for an organisation with the clumsy name Climate KIC. It’s a rather unusual beast—part granting agency, part community organiser, part public policy experiment—with the broad mission of addressing climate change through systems innovation. When I try to explain to people what we do, I can often sense a feeling of unease in my listeners. That’s because my organisation’s mission isn’t easily understood. Making sense of it requires careful listening, deliberate contextualisation, and a commitment to engage in a dialogue. In short, it requires people to make an effort.

One reaction I often get in such conversations is a demand for a succinct mission statement. “You must have an elevator pitch!,” they insist. I disagree. Not because some noble causes cannot be succinctly defined. But because reductionist strategies that make for easy conversation are likely to be inadequate to address the most complex challenge humanity has ever faced.

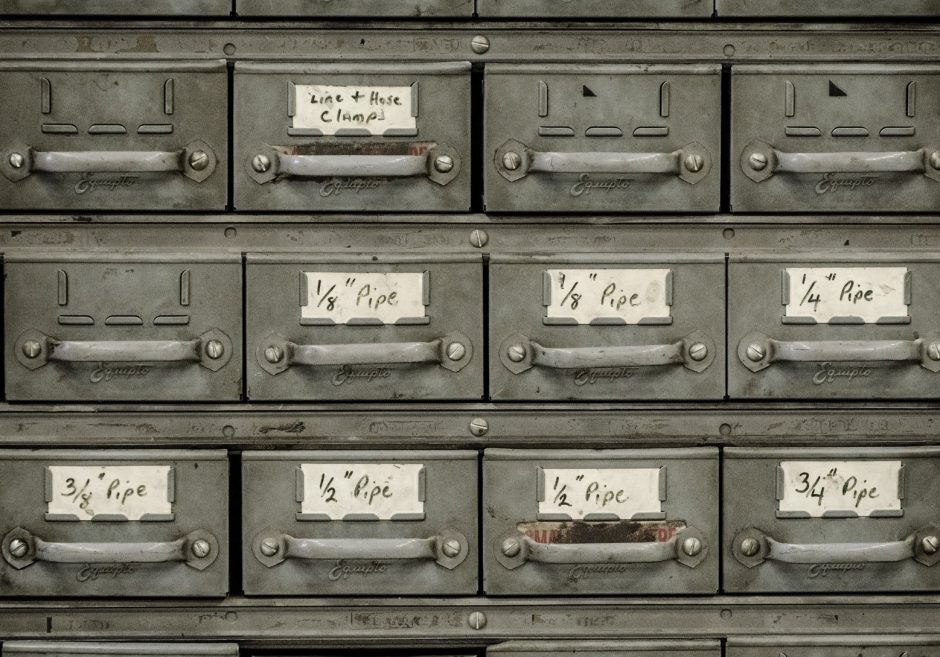

The psychological force at play here is a need to categorise—to fit things into neatly defined, clearly labeled boxes. In times of increasing complexity, such categorisation can be extremely useful, creating order in a world that is fundamentally messy and establishing structures so that we can better organize, analyse, and manage it.

The problem arises when categorisation limits our ability to understand and respond to issues that require systemic thinking, cross-disciplinary analysis, and collaborative action. Climate change, like other grand challenges of our time, is a complex issue that defies categorisation. Yet we often approach it with mindsets and practices that are steeped in rigid classification.

As we enter the “decisive decade” of the 21st century, the time has come to redefine our relationship with categories.

Why we categorise

The world around us is infinitely complex, so we categorise to simplify. In biological evolution, distinguishing between predator and prey is the key to survival. The modern analog is the neatly organised supermarket, in which all products are grouped by classes and variants so that customers can find the items on their shopping lists with ease.

Creating order allows us to develop shortcuts, saving us from having to sort through a large set of strategies for solving real-world problems. When devising a plan for crossing a busy street, for instance, we group all vehicles into a single class of “dangerous moving objects” irrespective of their colour or make. The benefit of such heuristics is that they reduce our cognitive load, making space for other tasks—like sipping a cup of coffee and listening to your favorite podcast—whilst (safely) crossing the street.

Categorisation also serves as a source of identity. Just consider the tribal pride carried by doctors, bankers, firefighters, social workers, and other members of distinguished professions. That’s because such groups operate under a set of paradigms, worldviews, values, and methods that discern them from others, creating a feeling of community and belonging.

Finally, categorisation facilitates specialisation. Adam Smith, the father of modern economics, saw the division of labor as a key to economic prosperity. Today, categorisation is omnipresent in economic life, and we find a dizzying array of classifications—and self-proclaimed experts—in business disciplines such as law, tax, finance, audit, and marketing.

“So, what’s the problem?,” you may ask.

The problem with compulsive categorisation

Categorisation becomes dangerous if it leads to an incomplete understanding of the problem. Analysts steeped in specialised mindsets will frame a problem from narrow, incomplete perspectives. Climate change, though long recognised as a “wicked problem”, is still often framed either as a technological, economic, or political issue depending on whether the analyst is an engineer, policymaker, or economist.

The consequences materialise in ineffective response strategies. The World Economic Forum advocates that we focus on technologies, the Stern Review makes a case for anchoring the debate in discount rates, the magazine Foreign Policy suggests we fix our political system, the Stanford Social Review invokes the idea of a culture war, and Mark Carney sees the root cause of our problem in the short-termism of present-day capitalism. Collectively, these explanations form a coherent whole. On their own, however, each paints an incomplete picture.

In my work, I experience the limiting effects of categorisation on a daily basis—when observing attendees at a World Bank conference cling to a rigid distinction between the public sector and the private sector, when hearing from civil servants in Amsterdam how the city’s departmental structure creates siloed thinking and action, when people ask me why Climate KIC also cares about biodiversity and gender equality, given that climate action is boxed into Sustainable Development Goal no. 13, when we speak to multilateral development banks about strategic portfolios and are told that they are only interested in single-asset investment opportunities, and when I try to make sense of the EU’s new taxonomy on sustainable finance, which is based on the 996 categories of the NACE industrial classification system.

How we frame a problem matters because it determines which disciplines we call upon, which people we invite, which vocabulary we use, which methods we deem valid, and which norms we find acceptable.

Herein, then, lies the tyranny of classification: The borders we draw for ourselves create a prison of thought and collaboration, inhibiting movement, connectivity, and learning.

What we would gain from letting go of boundaries

Dissolving boundaries will let us see relationships, interdependencies, and feedback loops. It will open doors to travel between intellectual and cultural worlds, allowing us to take other people’s perspectives and learn how to speak their language. It will encourage us to imagine novel combinations of actors and transactions, renewing our appreciation of the wonderful multidimensionality of our world. It will inspire us to redefine notions of value and virtue. And, importantly, it will lead us to lift the locus of interest from the individual category to the system as a whole, providing new perspectives on priorities and responses.

We can all contribute. Schools could teach the fundamentals of systems thinking and design their curricula in a way that highlights topical relationships and encourages inter-disciplinarity, as Harvard University has recently done. Managers could rethink incentive systems to promote collaboration and adjust their recruitment practices to place more value on inter-disciplinary and generalist skills, as David Epstein argues in his book Range. Journalists could de-emphasize the meme of the “hero” and “expert” and instead focus more on the accomplishments (and secrets) of teams, organisations, and movements.

Yet, arguably the most powerful action we can all take is to raise our awareness of when we might fall victim to the tyranny of categorisation. So next time you look at a problem, ask yourself: How else might you frame it? What other perspectives could you take? What insights would you gain from seeing it as a multi-categorical issue? What combination of actors would offer the promise of resolution? What multiple response strategies could there be?

We all sit in boxes, all the time. To address the most pressing challenges of the 21st century, we need to grow just enough to peek over the wall, climb to the other side, and start exploring.