Water scarcity in Southern Europe: Problems and solutions

Climate KIC partner the Transformative Innovation Policy Consortium (TIPC) is a group of science, technology and innovation researchers, policymakers and funding agencies working together to give substance to a new framing for Science, Technology and Innovation (STI) policy—Transformative Innovation Policy (TIP). This blog post, part of TIPC’s “Making the Green New Deal happen series,” is authored by Climate KIC’s Community team member Eva Enyedi, and examines the causes, challenges and solutions of water scarcity. Read on for a lightly-edited version of TIPC’s original post, which first appeared on its website.

Water scarcity causes and challenges

As I write this blog, news about a severe drought in the Po Valley is on the front pages of European newspapers. The water shortage is forcing authorities to introduce water rationing for citizens in 125 municipalities and halting water use for irrigation. This historical drought is driven by the fact that there has not been any rain in the last 100 days, and there was not enough snow during the winter that could replenish the water reserves. The impacts of climate change, including higher temperatures and altered precipitation patterns, change the freshwater supply. Still, the drought is also exacerbated by the increased demand for water during the same period. This is where the concept of water scarcity becomes useful. Water scarcity and drought are interconnected, but they are not the same. In contrast to drought, water scarcity is not a temporary crisis but rather a structural imbalance between available water and demand, which changes with the seasons and the changing nature of economic activities.

The climate and water crises are inherently interlinked in more ways than is immediately apparent. The scarcity of water has an impact on society, the economy and the environment, which compete for water. While it is clearly understood that people need water (for drinking, cooking and hygiene) and agriculture needs water for irrigation, the role of water is largely invisible in energy generation and industrial use. Agriculture is the largest user of freshwater in Southern Europe, varying between 50 per cent in Italy and 80 per cent in Greece, followed by industrial and urban use, including tourism and commercial activities. Finally, water scarcity damages the environment, biodiversity and ecosystem services. Unfortunately, examples abound about natural ecosystems being damaged and sometimes destroyed entirely by the over-extraction of water for human use. With the increasing episodes of water shortages, policymakers in Europe need to plan for a more water-scarce future, where there is a more balanced water distribution between human and natural ecosystems.

Water scarcity has complex reasons; however, the following four stand out in Southern Europe:

- There is less available water when it is most needed: In general, more water is needed in the warmer months due to increased tourism and agricultural production; however, these are when Southern European countries receive less precipitation. On the other hand, there is still a massive amount of freshwater wasted through leakages in the water infrastructure or by wasting food that requires large amounts of water to be produced.

- Water is polluted: Human activities, including agriculture, industry and urban use, generate pollutants that are not sufficiently removed by water treatment plants. This happens for two reasons: The technical difficulty of removing contaminants and the associated cost or because of lax regulation and enforcement by the authorities.

- There are solutions, but they are not applied: In the last ten years, there have been many scientific breakthroughs for making water treatment smarter and more circular. These solutions offer opportunities for using digital solutions, AI and remote sensing to use water more efficiently and by reusing treated wastewater for irrigation and recovering energy and nutrients from wastewater. The reason why these have not been widely applied are manifold, including the lack of skills from companies to apply them, risks related to contaminants and pathogens in wastewater, and lack of guidance for their application and business plans to ensure the return on investment.

- Low level of good governance and cost recovery: Water is scarce, and its treatment is costly; however, it is being treated as an abundant and cheap resource. The failure to see the actual cost associated with the use of water in Southern European societies contributes mainly to the lack of economic incentives for saving water and using it for the most valuable activities.

Water scarcity solutions

The solutions that have been applied aim to increase the supply of good quality water and reduce its demand. Southern European countries are at the forefront of water scarcity, and how they apply solutions to it can offer valuable lessons to other regions that will become water scarce in the future.

Reuse of treated wastewater: Water treatment plants are increasingly collaborating with the agricultural sector to reuse treated wastewater for irrigation and replenishing aquifers. One outstanding example is the region of Murcia, Spain. This region is one of the driest in Spain, while it generates 20 per cent of the country’s agricultural output and has a booming tourism sector, depending on water availability. ESAMUR, the Entity for Sanitation and Treatment in the Region of Murcia, reuses virtually all the wastewater it treats for irrigation and replenishing aquifers as an effective measure to save water and energy.

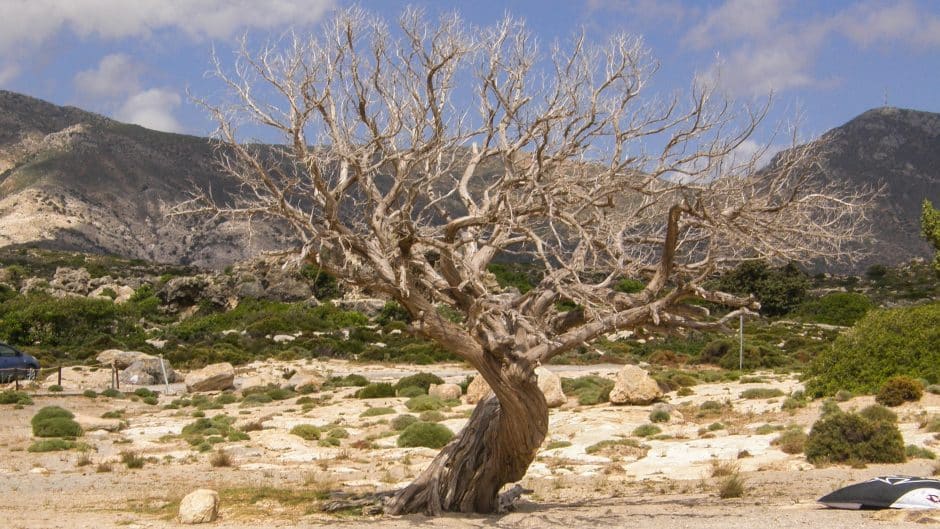

Photo via the Tinos Eco Lodge website.

Combination of nature-based solutions with conventional infrastructure: The Tinos Eco Lodge demonstrates how to combine innovative water management methods and generate renewable energy while doing agricultural and touristic activities. The ecolodge is located on the island of Tinos, in the Aegean Sea, in Greece, where freshwater resources are traditionally scarce. Still, the careful management of water resources has become even more critical due to the increased number of tourists, agricultural activity and climate change. The ecolodge captures rainwater and air humidity through condensation units and treats wastewater generated by the guests of the ecolodge through a constructed wetland. This new source of water, also called reclaimed water, is then used to irrigate an organic, permaculture garden to provide food for the guests and local markets. This touristic facility is off-grid and generates its renewable energy through solar panels. The ecolodge serves as a demonstrating site within an EU-funded project and is connected to replication sites.

Using technology to save water: Technological solutions are increasingly used both in agriculture and urban water management to save water. To give some examples, Agrowanalytics, a Spanish start-up, combines irrigation scheduling, monitoring and analysis to irrigate with the amount of water a particular crop needs and when it needs it most, achieving up to 30 per cent saving on water. Shayp, another start-up from Belgium, focuses on reducing water waste in buildings through leaks and bursts in pipes, using a platform for real-time flow analytics and remote sensing.

Governance and finance solutions to save water: Water governance is a very complex issue, but that is a positive example when the collaboration of stakeholders leads to improved water distribution. The example of the Eastern La Mancha aquifer shows that close collaboration between farmers, municipalities and the river basin authority achieved a more sustainable use of water. The collaboration included a clear definition of the agents, monitoring and data and conflict resolution mechanism. Another good example is a combination of an increase in water cost, billing the exact amount used, and water-saving equipment that has achieved a 25 per cent saving in irrigation water in Spain[1].

The application of these solutions is hindered by structural problems in the water sector, such as lack of investment and lack of skills to apply new solutions, but also by political and social risk associated with higher water prices, more stringent control of water use, and the use of lesser quality water for non-drinking purposes, such as irrigation, cleaning machinery and streets.

The application of these solutions offers opportunities not just for tackling water scarcity but also to support climate mitigation and adaptation measures and benefit the environment. Nevertheless, water is not central to the EU Green Deal, the plan that leads the EU’s response to climate change, and is marginal in the national and subnational climate strategies. While policymakers are still defining the role of water in net-zero societies in Europe, periodic episodes of water crisis such as the one in Italy reminds us of the importance of caring for water, one of the most important resources we have.